This Ain’t No Party, This Ain’t No Disco

I’ve been thinking lately about the Talking Heads. My husband and I have a fondness for Naïve Melody, and the phrase “this must be the place” has been popping up unexpectedly. Perhaps more relevant to the current moment though is Life During Wartime; a whimsical, chaotic ditty about a character who is finding his world increasingly violent and unrecognizable, with a fear that the party is over and he “might not ever get home.”

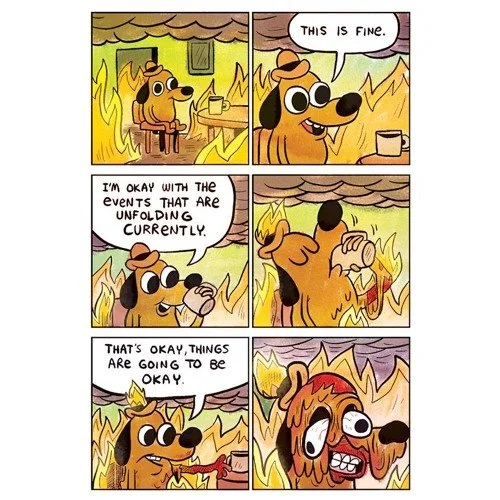

David Byrne likes lamp. IYKYK

My original plan for Downshifting was to offer evidence, ideas and inspiration around a life that could release itself from the viselike grip of hustle culture and pursue quality over quantity. I envisioned biweekly posts where I described a challenging phenomenon, like last issue’s “emotional parkouring”, and then I offered hopeful strategies, like micro-joy, all in the name of slowing down and choosing being over doing.

In the weeks since my inaugural issue, I’m feeling increasingly like the unmoored protagonist in “Life During Wartime”; I’d like to talk to you about slowing down and unwinding internalized capitalism, but “I aint got time for that now.” Our nervous systems are collectively overwhelmed by mass trauma and I have felt, plainly put, stuck.

The work of psychotherapy, particularly in trauma, is to help clients identify stuck points and move past them. We do this in the safety of a strong therapeutic relationship, partly by finding soft spots in the narrative where a reframe might be effective, and harnessing strengths and resources. I’m reminded that the greatest predictor of post-traumatic recovery, and most protective factor against the development of PTSD, is social support and connectedness. Connections to other people and sense of community actively down regulate the nervous system, because we are wired to attach. In this way, connection is both healing and preventative, and is as it happens, a valuable part of downshifting.

It may also save your life.

The “neighborism” occurring in the Twin Cities during the current ICE occupation is nothing short of magnificent. There are people of all backgrounds finding each other on Signal chats and using codenames in public, showing up with whistles, delivering groceries and doing the dangerous but essential work of recording the truth for the public record. The famous psychotherapist Esther Perel describes intimacy as not only personal but civic, and as a “willingness to be implicated in another person’s safety and dignity.” It is the height of connection to stand for your neighbor, and it is exactly what we are wired to do.

My cross-cultural work and my desire to downshift intersect through the lens of liberation psychology; our personal wellness is tied to our collective freedom. Whether it be freedom from internalized capitalism that demands endless “production” or freedom from state terror, our individual wellness is tied to those of our neighbors.

In that spirit, your downshifting journal prompt is below, and you may choose what calls to you:

Ye olde Journal that will Change my Lyfe

To whom do you feel most connected to? What allows you to feel connected to this person?

Is there someone in your community you’d like to know? A neighbor you see in the elevator but never speak to, somebody who is always at the coffee shop when you pop in, a parent you wave to at drop off but don’t really know? Tell us a bit about this person and why you want to know them.

Your downshifting action item is if you choose option 1, share your response with the person you feel connected to. If you choose option 2, challenge yourself to reach out to this person. It could simply be saying hello and offering a smile. We are wired for connection, and we are socialized for individualism.

If I bring us back to the Talking Heads, I’m reminded that the second to last verse of Life During Wartime may be just as relevant as the others:

“You make me shiver, I feel so tender.

We make a pretty good team.

Don’t get exhausted, I’ll do some driving.

You ought to get you some sleep.”

Till next time,

~S

Miscellaneous Musings

I derived a great deal of meaning and connection when I collaborated with my friend and colleague Dr. Cassidy Freitas on this podcast and guide about how to continue parenting during this dark moment: The World Isn’t Okay, and We’re Making PBJs.

My micro joy is often silly and shared, and so my kids and I have been singing this tune by 2Krispii: Dinosaur for President

Support Minnesota with resources and ideas here, and don’t underestimate the value of sending a love note to a Minnesotan. Neighboring is not just on your block, and connections between people existed before borders and nations ever did.

Downshifting in Dystopian Times

Spoiler: It’s not fine.

I’ve never played parkour, but I think we are all emotional parkourists now. Let me explain.

Parkour is a sport characterized by moving efficiently through complex environments using tactics like running, jumping, climbing, and rolling. Rooted in military training, its philosophy is as much psychological as it is physical: parkour is about adapting—again and again—to rapidly changing demands.

My original inspiration for this blog, called Downshifting, came from a mix of personal and professional experiences that taught me something essential: quality of life matters more than quantity of output. It is precisely because we are parkouring through dystopian times that we must chose where to place our attention, money, and very precious, finite time on this planet.

Our nervous systems are not built to witness the brutal murder of a mother at point-blank range at the hands of an ICE agent, then immediately switch gears to making spreadsheets in the Spreadsheet Factory, then pivot again to summer camp sign-ups, Hollywood awards season, and influencers hawking protein shakes. For those of us with the privilege of being observers rather than direct participants, the parkour is largely mental. But for countless others, it is a full-body extreme sport with real and immediate consequences.

We often think of “multitasking” as doing multiple physical tasks at once—texting while driving, or the more benign sending an email while half-listening on Zoom. What we don’t tend to think about is the cost of constantly parkouring between emotional and cognitive states. Yet research has long identified something called switch cost: the time and energy the brain needs to disengage from one demand and shift to another.

Closely related is switch readiness, which describes the conditions that make switching easier and reduce that cost. Switch readiness increases in emergencies and truly essential situations—but it declines sharply when tasks are intense, demanding, or emotionally charged.

Are you seeing where I’m going with this?

Emotional parkouring isn’t just “being busy.” It’s a specific kind of relentless, high-dissonance shifting between emotionally intense states. Even for those who actively avoid the news, the effort required to disengage and protect oneself is its own form of parkour.

We are parkouring with high switch cost and it’s draining our already low batteries. This may be worse for those who are already anxious, but it isn’t really good for any of us. We often begin our days already in switch debt, in sleep debt, already low on bandwidth. Then we continue to spend what little we have responding to the demands of the day.

If we want to survive—and live well—we have to downshift demands in order to allocate bandwidth.

The antidote to macro-overwhelm is micro joy. The Big Joy project , a large-scale multinational citizen science initiative, is producing early and promising data: just seven minutes a day of micro-joyful acts can lift mood and increase feelings of connection. Micro-joys are small, attainable moments of peace, meaning, connection, or fun. They remind us that positive emotions are still possible and keep those neural pathways open and responsive.

Ideally, micro-joys are simple and accessible—which means they carry low switch costs. More importantly, they offer a high return. They help replenish the energy required for emotional parkour.

So, with all that in mind, here’s your 3 minute reflection prompt:

Close your eyes and picture the last time you experienced real joy. Don’t overthink it—trust your memory to take you someplace meaningful. Take a mental picture of this moment, open your eyes, and describe it in a few sentences in your journal. What are the sights, sounds, smells, and textures of this memory? What made it joyful?

Let’s close out with some micro-joys. What are you reading/watching/listening to right now?

Reading: I’ve recently discovered Gillian MacAllister’s twisty, page turning thrillers and Famous Last Words is hitting the sweet spot.

Watching: I will finish Stranger Things. I will.

Listening: The internet knows I’m a Xennial and keeps feeding me Television Dreams and I’m eating it up. Sorry not sorry.

Thanks for downshifting with me, and see you next time. ~S

Welcome to Downshifting: Musings on Burnout, Culture, Mental Health and More

Do any of us really know how to slow down?

Mentally, shouldn’t we all be here?

Downshift: verb

down·shift ˈdau̇n-ˌshift

1: to shift an automotive vehicle into a lower gear

2: to move or shift to a lower level (as of speed, activity, or intensity)

I want to be honest; the title of this blog is as aspirational for me as it is for you. I long to downshift, or perhaps more accurate, I long to long to downshift. I feel it in my bones that slowing down and being more present is right for me — yet I’ve internalized hustle culture in ways that put me in conflict with myself when I try to take my own advice.

I’ve been grateful for the small but engaged Instagram community that I’ve been building in recent years; folks from all walks of life who are interested, at least somewhat, in ideas on how to slowdown, prevent burnout, validate their experiences, and feel better. I eventually reailzed that cute videos and short captions are limiting, and as a talker, I knew I had so much more to say. Perhaps more than that, I wrapped yet another year of working with a wide range of clients, all of whom at some point mentioned feeling overwhelmed, overworked and depleted.

Are we all beginning a new year feeling wrung out? Does anybody actually know how to slow down, or are we all just pretending, performing, posting cozy pictures of reading by the fire when our brain is everywhere but here?

I’d like to downshift, and I think you would too. But in a society whose values are psychologically and economically shaped by capitalism, we are socialized to believe that our self-worth rests in our output, our productivity, and our ability to commodify our creations. It’s not surprising that this and other pressures have made it hard to feel good about slowing down.

“Downshifting” is my somewhat clunky but thoughtful and deeply human attempt to wrestle with questions on how we slow down in a culture that demands us to speed up. As a clinical psychologist, I hope to integrate research and expertise based ideas into this conversation. As a lifelong overfunctioner, I hope to learn while I teach, because we’re in this together.

Downshifting will be posted every two weeks with musings on burnout, culture, mental health and more. I’ll include actionable strategies on how to check in on your pace and practice slowing down, and maybe some links and resources with a dash of dry humor on top.

This is a space to question the pace we’ve inherited — and to imagine something kinder.